So I went to see Thor: Ragnarok this weekend, with a colleague who knew nothing except a) there’s a god named Thor, b) he has a brother named Loki, and c) no, really, that’s about it. I liked it. It’s a fun film. I’m going to spoil the hell out of in the column that follows.

The thing that struck me the most about Thor: Ragnarok is that it is the first example of a film superhero doing something that comics superheroes have been doing for about 40 years now, namely: going to space to reinvent or rediscover themselves. The defining example of this is almost certainly during Alan Moore’s run on Swamp Thing, but I think the first example might be the X-Men’s late ‘70s foray into space, where they met the Starjammers and kicked off the first half of the Dark Phoenix Saga. (I don’t think the Kree/Skrull war counts because while there’s no particular reason the Avengers wouldn’t go to space, the X-Men’s mission — mutant-human relations — is inherently Earth-based, so going to space is "leaving their beat.")

For you Joseph Campbell fans out there, space is the wilderness, the liminal space where our hero goes and where ordinary laws no longer apply. When I say “ordinary laws” I don’t just mean social rules, though that is true; I also mean the thematic rules that normally apply to the hero, and which we have come to expect from previous adventures. Spider-Man web-slings his way across skyscrapers and under bridges, so when he finds himself in a suburb (as we saw to humorous effect in Homecoming), he’s entered a liminal space where he not only is able to act in unusual ways, he’s actually required to. The first Thor film, directed by Kenneth Branagh, established the Shakespearean quality of the character: a family conflict fueled by envy, dignity, and the brashness of youth. It established the Falstaffian comedy relief characters and a love story that bridges two worlds. These are all the ground rules for Thor, and by the end of Dark World they were rules which many audiences were simply tired of. (I'm not one of them.) But how do you get rid of all those things while still keeping Thor?

Spaaaaaace!

There is a big incentive for creative teams to take their characters into outer space: it is a place to avoid continuity. When you send Swamp Thing, Superman, the X-Men, or the Hulk into space, it means you don't have to worry about your character being asked to appear in the next crossover event. The old supervillains aren't going to show up, and you've left your entire supporting cast behind. As a creator, you have a blank canvas to create whatever new characters you want -- not to be permanent additions to the cast, but to exist temporarily and highlight or contrast characteristics of your protagonist. Space is infinite, and you can invent as many new worlds and new alien species as you want, and you don't even have to keep track of them. Leave that to the wikipedia contributors.

There are of course exceptions — Byrne’s Fantastic Four was at home in space, and they went there not to avoid continuity but to wallow in it and celebrate it — but Moore was definitely doing this when he sent Swamp Thing into space and later writers would follow his lead. When William Messner-Loebs began to write Wonder Woman, he admitted that he didn’t really understand how to write her or what she stood for, so he asked his editors if he could send her to space, and he specifically invoked Moore’s Swamp Thing when he did so. His hope was that, by taking Diana away from Paradise Island, the Justice League, and all the supporting cast and villains Perez had been using for a hundred issues, Messner-Loebs could focus on Diana by herself and, in the process, get a better handle on the character.

But Messner-Loebs wasn’t writing Swamp Thing and he wasn’t writing in the 80s. He was writing Wonder Woman in 1992, when the summer crossover was God and comics were already being written in easily-digestible story arcs for the trade paperback market. The Death of Superman was soon to come. So Wonder Woman’s sojourn in space was cut short by DC editorial after six issues, and we got the Contest instead (another way to accomplish the same thing: put the character under a microscope, figure out what she stood for, and jettison old continuity). When John Byrne left the three Superman titles he’d been writing, Jerry Ordway, Roger Stern, and Dan Jurgens immediately launched the Man of Steel into the “Exiled” storyline where, divorced from Neron’s “Underworld Unleashed” crossover and all the rest of his supporting cast, he could figure out what he really stood for and who he really was. (Like Thor and Hulk, he also got caught up in gladiatorial combat, which seems to be something of a SF theme at least as old as TOS's "Arena.")

All of this has been from the perspective of creators, but the journey to space can also create some great internal drama in the protagonists themselves. My F5W (Fellow 5th Worlder) Jerry Franke has compared this to the way Americans travel to Paris as a way to find themselves, what David McCullough called The Greater Journey. Whether he wants to or not, Hulk often finds himself far from Betty, Thunderbolt Ross, and Rick Jones. But no matter where you go, there you are, and when all our friends and relations, our archenemies and everyday problems are taken away, we are forced to reflect. We ask ourselves, "Who am I, really?" And in this version of the story, it takes us a long time to find the answer, but we're usually pretty happy with it once we do find it. These are stories that are about identifying your own innate qualities and celebrating them, defending them against the uninterruptible contempt of our times.

Sometimes, however, the goal is not introspection, it's reinvention. Instead of asking ourselves, "Who am I?", we ask, "What are the best parts of me? What can I shed, and what might I accrue?" Now, every creator has a different answer to this question, and fans are going to hate the answer no matter what that answer is, but it makes for some pretty interesting stories. You see this in Thor: Ragnarok when the God of Thunder tries to explain his relationship to his hammer -- complete with phallic symbology and a nod to the illogic of throwing a hammer really hard in order to fly. And you see it when he ends the movie with an eyepatch; for Thor, one of the answers to "What is the best part of me?" is "The part of me that comes from my father." And his recognition of that, his father's wisdom, becomes a red badge of courage worn on the face.

I don't think it's a coincidence that these space walkabouts often happen when a new creative team comes on board, especially when the last team has been working the character a while. Going to space is a great place to reinvent yourself in superhero comics, and Planet Hulk is a recent, very successful, example. When the Hulk returned from Sakaar, he was more popular than he’d been in decades and had a whole new supporting cast, spawning Red Hulks and Red She-Hulks and, well, I really want to see a Giant-Size Amalgam Spectacular with Orange, Yellow, and Indigo Hulks. Don’t you?

Lately, however, characters have taken their walkabouts here on Earth instead of space. Sometimes there's a good reason for this: the character symbolizes America itself, and the best way for such a character to "find himself" is the venerable American tradition of the "road trip." And so Captain America has traveled America often enough that it's become one of his things, a trope in use this very month, as Mark Waid kicks off another run on the title.

Symbols, however, are up to interpretation. I've already mentioned Superman's sojourn in space, but to J Michael Straczynski, Superman is an American superhero and, if he's going to find himself anywhere at all, it's not going to be in space. It's going to be walking across America, and so we got "Grounded." (Though, as many of you are already grumbling to your screens, JMS did not see fit to finish the story arc and in fact quickly abandoned it.)

These patriotic examples are exceptions — they avoid space because the object of their examination is the ground underneath their feet, the United States itself. I suspect most other terrestrial journeys of self-discovery happen for the same reason Messner-Loebs couldn’t keep Wonder Woman in space: there are too many expectations of continuity, too many crossovers to appear in. Few writers have the editorial power to escape corporate gravity and make it to space for a year.

Thor’s launch into space fits the pattern. Until now, Thor has universally been considered the weakest series in the franchise. Much like the freedom Moore had when he came to Swamp Thing — a title whose sales could not get much worse — Taika Waititi enjoyed a liberating freedom to reinvent Thor and jettison anything he didn’t want to use. In other words, this wasn't a "find yourself" space story, it's a reinvention space story.

(A moment of silence, if you please, for the sudden, silent, and ignominious death of Volstagg and Fandral, the only slightly less embarrassing Hogan, and the entirely absent Sif and Jane Foster? I’m not complaining about the movie — as I said, I enjoyed it — but I was disappointed that these characters, with all their narrative investment, were shuffled off so casually.)

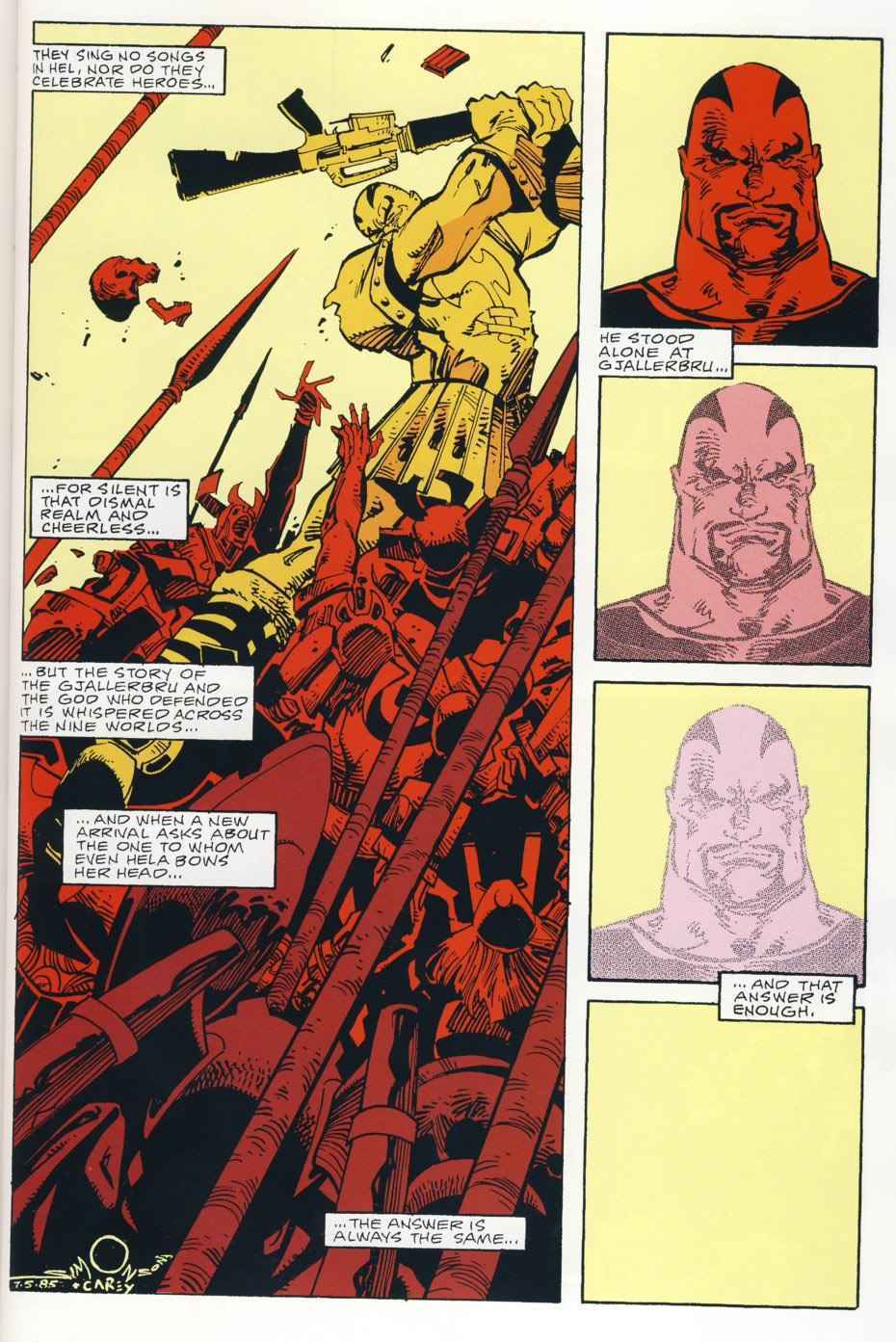

(And while I'm here, I want to note that, as entertaining of a film as this is, and as endearing as Karl Urban's Skurge is, Thor: Ragnarok’s greatest failing is that it sets up "He Stood At Gjallerbru" from Skurge's very first appearance and then completely fails to deliver on it. I mean, you have a bridge right there, and everyone has been laughing at Skurge, including us. And you could have just done it. It would have been gutsy and amazing and totally unexpected. This movie makes a swing at that quintessential tale and totally whiffs it. They should never have even bothered with the head-fake. I am done.)

This reinvention can even be vocalized, so that Thor wonders out loud about himself, his future, his decisions, and his powers. There was a time when the creators of superhero comics writers had a lot of leeway, where they could experiment with a book for a year or so and see how fans reacted. That time has passed, but the muscle of directors like Waititi allows them to recapture a bit of that freedom, especially when working on characters perceived as “the weakest link.”

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has continuity, but new movies are slow to come out and contractual obligations ensure that Thor can’t show up in too many more movies anyway. Imagine, for a minute, if there was a cap on how many times Wolverine could appear in a Marvel comic over the course of, say, a year; you’d have long stretches in which he would be stuck in his own title, having solo adventures. This is the effect actor contracts have on Marvel’s films, and it frees characters up from continuity. It means they don’t have to hang around Stark Tower for their inevitable cameo.

This post isn’t a real review. We here at Fifth World are planning another round table to discuss Thor, and you’ll get more from everyone then. But I’ve been thinking about the way cinematic Thor uses, for the first time, this device we’ve seen many times before in comics. I’d like to see Marvel and DC learn from this, and maybe bring "The Greater Journey" back into the toolbox for comics creators as well as for filmmakers. It’s not just a superhero tradition, it’s a really useful creative tool that allows a writer and artist to focus on their protagonist, minimizing all other distractions before bringing the character back down to Earth with a clearer vision, a strong self-image, and maybe some creative new twists like a supporting character or two.

Jason Tondro is an Assistant Professor of English at the College of Coastal Georgia, where he teaches comics & graphic novels, writing, and British Literature. He is the author of Superheroes of the Round Table: Comics Connections to Medieval and Renaissance Literature and various RPG resources, including The Deluxe Super Villain Handbook. He’s currently editing Arthur Lives! an urban fantasy RPG using the Fate system.

The thing that struck me the most about Thor: Ragnarok is that it is the first example of a film superhero doing something that comics superheroes have been doing for about 40 years now, namely: going to space to reinvent or rediscover themselves. The defining example of this is almost certainly during Alan Moore’s run on Swamp Thing, but I think the first example might be the X-Men’s late ‘70s foray into space, where they met the Starjammers and kicked off the first half of the Dark Phoenix Saga. (I don’t think the Kree/Skrull war counts because while there’s no particular reason the Avengers wouldn’t go to space, the X-Men’s mission — mutant-human relations — is inherently Earth-based, so going to space is "leaving their beat.")

For you Joseph Campbell fans out there, space is the wilderness, the liminal space where our hero goes and where ordinary laws no longer apply. When I say “ordinary laws” I don’t just mean social rules, though that is true; I also mean the thematic rules that normally apply to the hero, and which we have come to expect from previous adventures. Spider-Man web-slings his way across skyscrapers and under bridges, so when he finds himself in a suburb (as we saw to humorous effect in Homecoming), he’s entered a liminal space where he not only is able to act in unusual ways, he’s actually required to. The first Thor film, directed by Kenneth Branagh, established the Shakespearean quality of the character: a family conflict fueled by envy, dignity, and the brashness of youth. It established the Falstaffian comedy relief characters and a love story that bridges two worlds. These are all the ground rules for Thor, and by the end of Dark World they were rules which many audiences were simply tired of. (I'm not one of them.) But how do you get rid of all those things while still keeping Thor?

Spaaaaaace!

There is a big incentive for creative teams to take their characters into outer space: it is a place to avoid continuity. When you send Swamp Thing, Superman, the X-Men, or the Hulk into space, it means you don't have to worry about your character being asked to appear in the next crossover event. The old supervillains aren't going to show up, and you've left your entire supporting cast behind. As a creator, you have a blank canvas to create whatever new characters you want -- not to be permanent additions to the cast, but to exist temporarily and highlight or contrast characteristics of your protagonist. Space is infinite, and you can invent as many new worlds and new alien species as you want, and you don't even have to keep track of them. Leave that to the wikipedia contributors.

There are of course exceptions — Byrne’s Fantastic Four was at home in space, and they went there not to avoid continuity but to wallow in it and celebrate it — but Moore was definitely doing this when he sent Swamp Thing into space and later writers would follow his lead. When William Messner-Loebs began to write Wonder Woman, he admitted that he didn’t really understand how to write her or what she stood for, so he asked his editors if he could send her to space, and he specifically invoked Moore’s Swamp Thing when he did so. His hope was that, by taking Diana away from Paradise Island, the Justice League, and all the supporting cast and villains Perez had been using for a hundred issues, Messner-Loebs could focus on Diana by herself and, in the process, get a better handle on the character.

But Messner-Loebs wasn’t writing Swamp Thing and he wasn’t writing in the 80s. He was writing Wonder Woman in 1992, when the summer crossover was God and comics were already being written in easily-digestible story arcs for the trade paperback market. The Death of Superman was soon to come. So Wonder Woman’s sojourn in space was cut short by DC editorial after six issues, and we got the Contest instead (another way to accomplish the same thing: put the character under a microscope, figure out what she stood for, and jettison old continuity). When John Byrne left the three Superman titles he’d been writing, Jerry Ordway, Roger Stern, and Dan Jurgens immediately launched the Man of Steel into the “Exiled” storyline where, divorced from Neron’s “Underworld Unleashed” crossover and all the rest of his supporting cast, he could figure out what he really stood for and who he really was. (Like Thor and Hulk, he also got caught up in gladiatorial combat, which seems to be something of a SF theme at least as old as TOS's "Arena.")

All of this has been from the perspective of creators, but the journey to space can also create some great internal drama in the protagonists themselves. My F5W (Fellow 5th Worlder) Jerry Franke has compared this to the way Americans travel to Paris as a way to find themselves, what David McCullough called The Greater Journey. Whether he wants to or not, Hulk often finds himself far from Betty, Thunderbolt Ross, and Rick Jones. But no matter where you go, there you are, and when all our friends and relations, our archenemies and everyday problems are taken away, we are forced to reflect. We ask ourselves, "Who am I, really?" And in this version of the story, it takes us a long time to find the answer, but we're usually pretty happy with it once we do find it. These are stories that are about identifying your own innate qualities and celebrating them, defending them against the uninterruptible contempt of our times.

Sometimes, however, the goal is not introspection, it's reinvention. Instead of asking ourselves, "Who am I?", we ask, "What are the best parts of me? What can I shed, and what might I accrue?" Now, every creator has a different answer to this question, and fans are going to hate the answer no matter what that answer is, but it makes for some pretty interesting stories. You see this in Thor: Ragnarok when the God of Thunder tries to explain his relationship to his hammer -- complete with phallic symbology and a nod to the illogic of throwing a hammer really hard in order to fly. And you see it when he ends the movie with an eyepatch; for Thor, one of the answers to "What is the best part of me?" is "The part of me that comes from my father." And his recognition of that, his father's wisdom, becomes a red badge of courage worn on the face.

Lately, however, characters have taken their walkabouts here on Earth instead of space. Sometimes there's a good reason for this: the character symbolizes America itself, and the best way for such a character to "find himself" is the venerable American tradition of the "road trip." And so Captain America has traveled America often enough that it's become one of his things, a trope in use this very month, as Mark Waid kicks off another run on the title.

Symbols, however, are up to interpretation. I've already mentioned Superman's sojourn in space, but to J Michael Straczynski, Superman is an American superhero and, if he's going to find himself anywhere at all, it's not going to be in space. It's going to be walking across America, and so we got "Grounded." (Though, as many of you are already grumbling to your screens, JMS did not see fit to finish the story arc and in fact quickly abandoned it.)

These patriotic examples are exceptions — they avoid space because the object of their examination is the ground underneath their feet, the United States itself. I suspect most other terrestrial journeys of self-discovery happen for the same reason Messner-Loebs couldn’t keep Wonder Woman in space: there are too many expectations of continuity, too many crossovers to appear in. Few writers have the editorial power to escape corporate gravity and make it to space for a year.

Thor’s launch into space fits the pattern. Until now, Thor has universally been considered the weakest series in the franchise. Much like the freedom Moore had when he came to Swamp Thing — a title whose sales could not get much worse — Taika Waititi enjoyed a liberating freedom to reinvent Thor and jettison anything he didn’t want to use. In other words, this wasn't a "find yourself" space story, it's a reinvention space story.

(A moment of silence, if you please, for the sudden, silent, and ignominious death of Volstagg and Fandral, the only slightly less embarrassing Hogan, and the entirely absent Sif and Jane Foster? I’m not complaining about the movie — as I said, I enjoyed it — but I was disappointed that these characters, with all their narrative investment, were shuffled off so casually.)

(And while I'm here, I want to note that, as entertaining of a film as this is, and as endearing as Karl Urban's Skurge is, Thor: Ragnarok’s greatest failing is that it sets up "He Stood At Gjallerbru" from Skurge's very first appearance and then completely fails to deliver on it. I mean, you have a bridge right there, and everyone has been laughing at Skurge, including us. And you could have just done it. It would have been gutsy and amazing and totally unexpected. This movie makes a swing at that quintessential tale and totally whiffs it. They should never have even bothered with the head-fake. I am done.)

This reinvention can even be vocalized, so that Thor wonders out loud about himself, his future, his decisions, and his powers. There was a time when the creators of superhero comics writers had a lot of leeway, where they could experiment with a book for a year or so and see how fans reacted. That time has passed, but the muscle of directors like Waititi allows them to recapture a bit of that freedom, especially when working on characters perceived as “the weakest link.”

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has continuity, but new movies are slow to come out and contractual obligations ensure that Thor can’t show up in too many more movies anyway. Imagine, for a minute, if there was a cap on how many times Wolverine could appear in a Marvel comic over the course of, say, a year; you’d have long stretches in which he would be stuck in his own title, having solo adventures. This is the effect actor contracts have on Marvel’s films, and it frees characters up from continuity. It means they don’t have to hang around Stark Tower for their inevitable cameo.

This post isn’t a real review. We here at Fifth World are planning another round table to discuss Thor, and you’ll get more from everyone then. But I’ve been thinking about the way cinematic Thor uses, for the first time, this device we’ve seen many times before in comics. I’d like to see Marvel and DC learn from this, and maybe bring "The Greater Journey" back into the toolbox for comics creators as well as for filmmakers. It’s not just a superhero tradition, it’s a really useful creative tool that allows a writer and artist to focus on their protagonist, minimizing all other distractions before bringing the character back down to Earth with a clearer vision, a strong self-image, and maybe some creative new twists like a supporting character or two.

Jason Tondro is an Assistant Professor of English at the College of Coastal Georgia, where he teaches comics & graphic novels, writing, and British Literature. He is the author of Superheroes of the Round Table: Comics Connections to Medieval and Renaissance Literature and various RPG resources, including The Deluxe Super Villain Handbook. He’s currently editing Arthur Lives! an urban fantasy RPG using the Fate system.

Thor in Spaaaaace!

![Thor in Spaaaaace!]() Reviewed by Jason Tondro

on

Wednesday, November 08, 2017

Rating:

Reviewed by Jason Tondro

on

Wednesday, November 08, 2017

Rating: